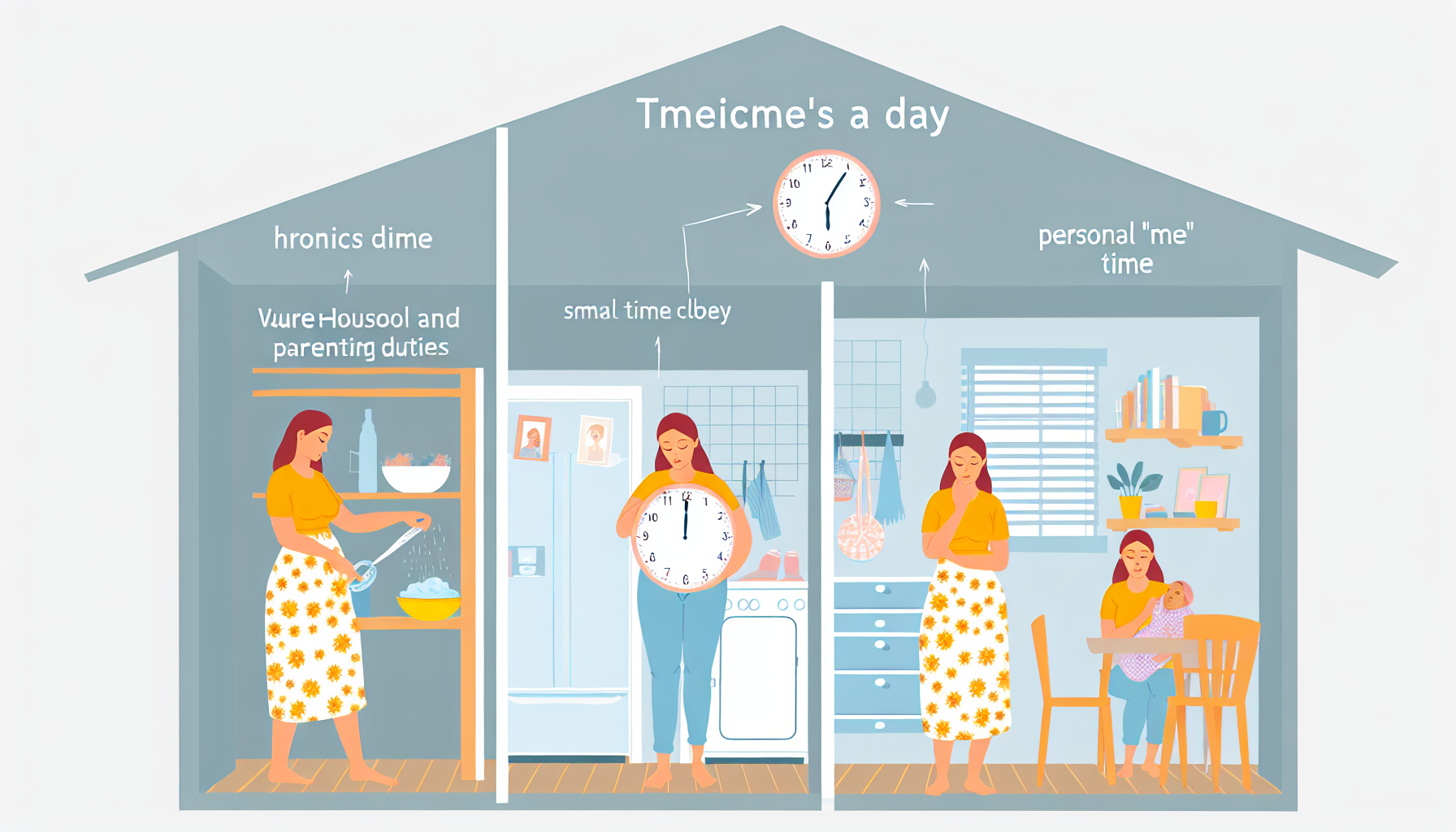

New mothers are getting far less “me time” than they need, averaging about one hour of restorative personal time per day, according to new research released this week. The findings point to a growing mismatch between the intense demands of early parenthood and the limited discretionary time available to recover, with implications for stress, mental well-being, and postpartum burnout risk.

Key Takeaways

– shows new mothers average about one hour of restful me time daily, with personal time accounting for under one-third of the day. – reveals activity tracking of 47 mothers and 22 interviews underscored stress, loneliness, and emotional exhaustion linked to constrained personal time. – demonstrates mothers spent about 60% of their day at home, with less than a third cataloged as discretionary or personal time. – indicates competing needs deprioritize exercise and self-care; a 12-woman study of babies under 12 months found “time for self” scarce and guilt-laden. – suggests U.S. moms’ “excellent” mental health ratings fell from 38.4% to 25.8% (2016–2023), heightening urgency for supports that expand me time.

New mothers average just one hour of me time a day

A 3 September 2025 research release led by Dr Thuy‑Vy Nguyen reports that new mothers typically achieve only around one hour of restful “me time” each day, with personal time representing less than one-third of the day overall. The mixed-methods project combined 22 qualitative interviews with activity tracking for 47 mothers, and warned that insufficient personal time fuels stress, loneliness, and emotional exhaustion associated with burnout in early motherhood [1].

For many, the rare minutes of solitude are fragmented and often interrupted, making true recovery hard to achieve. When personal time is constrained to brief intervals squeezed between childcare, household labor, and sleep, mothers have fewer opportunities to decompress, reflect, or engage in restorative activities.

The researchers stress that “proper me-time” is not a luxury but a recovery resource. Without it, daily strain accumulates, increasing the likelihood of emotional overload at precisely the moment when infants require round‑the‑clock care.

How mothers’ days stack up: at home, but not their own

Time-use snapshots from the study indicate that mothers spent roughly 60% of their day at home, yet less than a third of their day counted as personal or discretionary time. That mismatch underscores how being physically at home does not equate to having time that is one’s own; caregiving and household tasks dominate even in familiar spaces. Study authors called for better systems and supports so mothers can reliably access meaningful personal time and reduce burnout risk [2].

The distinction matters: “being home” can involve high cognitive load, continual vigilance, and rapid task switching. Without protected blocks for recovery, even quiet moments are haunted by the next feed, nap, or load of laundry—conditions that keep the stress response activated rather than releasing it.

When personal time shrinks, stress rises and burnout risk grows

The study’s warning about emotional exhaustion is consistent with a broader body of psychological evidence on solitude and self-regulation. When individuals can access autonomy-supportive alone time—time chosen, not imposed—they tend to see gains in self-regulation and, counterintuitively, lower loneliness. In this context, quality me time functions as a psychological “reset,” helping people replenish energy, reduce overload, and protect daily functioning when demands are high [4].

In early parenthood, that reset is especially critical. Nights can be fragmented by infant sleep needs, days punctuated by feeds and soothing, and cognitive bandwidth strained by logistics. Without restorative intervals, stress accumulates, making irritability, sadness, and feelings of overwhelm more likely. Over time, emotional exhaustion—one core dimension of burnout—can entrench, undermining well-being and resilience.

Self-care trade-offs in early motherhood: sleep, exercise, and me time

Another 2025 qualitative study offers a zoomed-in view of how new mothers triage self-care. Interviewing 12 women with babies under 12 months and applying the COM‑B behavior-change model, researchers found sleep was generally prioritized, while exercise and personal time were deprioritized or delayed. Crucially, “time for self” was often absent and accompanied by guilt, creating a psychological barrier even when small windows did open. The authors recommend targeted interventions to address barriers to postpartum self-care and bolster resilience [3].

These patterns help explain why an hour of restorative me time can be so elusive. When sleep deprivation is acute, any available minutes are likely to be allocated to recovery sleep or urgent tasks, not discretionary activities. Meanwhile, guilt and social expectations can erode the perceived legitimacy of carving out purely personal time, even when partners or community members are available to help.

Me time is a public-health issue, not a private luxury

Under the surface of individual routines lies a system-level question: who absorbs the time cost of care? When that cost is shouldered disproportionately by mothers, the deficit shows up as depleted personal time and cumulative stress. The new findings situate me time as a measurable determinant of maternal mental health and daily functioning, rather than a lifestyle preference.

That framing aligns with a broader deterioration in women’s mental health indicators over recent years. In one large analysis summarized for the public, the share of women rating their mental health as “excellent” fell from 38.4% in 2016 to 25.8% in 2023—nearly a 13‑point drop across a cohort of roughly 200,000 women. Experts linked declines to burdens including childcare, limited personal time, and financial stress, and called for policy action to expand mental‑health and parental supports [5].

Policy and community fixes to restore me time

Solutions to the me time gap require time, trust, and tangible support. The research points to several levers: – Scheduleable respite: Guaranteed windows—daily or several times per week—when another adult assumes care, allowing mothers to plan and protect true personal time. – Partner and family coordination: Explicitly distributing overnight duties, feeding logistics, and household labor to create predictable recovery blocks. – Community care: Low-cost neighborhood respite exchanges, postpartum doula access, and volunteer networks to smooth acute demand spikes. – Employer policies: Paid parental leave and flexible scheduling that reduce early return-to-work pressures and restore daily control. – Clinical screening: Incorporating questions about personal time into routine postpartum visits to identify at-risk mothers early and connect them to supports.

These interventions are not merely “nice to have.” They convert me time from an unpredictable leftover into a protected resource that supports emotion regulation, reduces cumulative strain, and improves the odds of sustaining exercise, social connection, and quality sleep.

What “quality” me time looks like in practice

The solitude literature suggests that quality matters as much as quantity. Autonomy—choosing what to do and when—is a key ingredient in making brief intervals restorative. Activities that replenish energy vary by person, but common themes include: – Quiet rest without multitasking – Brief walks or light movement in nature – Short bouts of creative focus or hobbies – Screen-free moments for reflection or journaling – Connecting with friends on one’s own terms

The goal is to shift from “stolen minutes” to purposeful recovery, even in short doses. Ten minutes of genuinely chosen solitude can reset mood more effectively than a longer, distracted interval riddled with interruptions or obligations.

Measuring progress: from minutes to outcomes

For families and systems, tracking me time can be as simple as logging minutes per day and noting perceived energy, stress, and mood. Over a few weeks, the patterns usually become clear: fewer minutes correlate with more overwhelm; more protected blocks correlate with better mood and patience. While research quantifies average availability, the practical task is to engineer reliable intervals that fit each household’s constraints.

Clinicians and community programs can incorporate quick me time audits into postpartum support: How many minutes are you reliably getting? What gets in the way? Who can help protect one more 20‑minute block this week? These micro‑targets translate population findings into everyday gains.

How this research was conducted—and its limits

The new analysis blended qualitative interviews with wearable or app-based activity tracking, offering a rare real‑time picture of how mothers’ days unfold. The sample sizes—22 interviews and 47 tracked participants—enable depth and specificity but do not represent the full diversity of new mothers, including those with multiple children, complex medical needs, or limited social support. Still, the consistency across qualitative narratives and observed time-use patterns strengthens the central conclusion: restorative personal time is scarce and fragmented in early parenthood.

Future studies can broaden samples across regions, socioeconomic groups, and cultural norms, and link time-use data to validated mental‑health scales to quantify how incremental gains in me time translate into reduced stress and burnout risk. Combining time diaries, wearable data, and ecological momentary assessments could clarify the dose–response curve for recovery.

The bottom line

Across interviews, time-use logs, and complementary qualitative studies, one pattern stands out: new mothers have too little me time, and what exists is often interrupted. The average—about one hour of restorative personal time per day—falls short of what many need to reset, leaving stress to accumulate during a period already defined by sleep disruption and high caregiving demand. Designing systems that reliably return minutes—and autonomy—to mothers is not indulgence. It is prevention.

Sources:

[1] Durham University – Study shows the lack of ‘me time’ for new mothers: www.durham.ac.uk/research/institutes-and-centres/medical-humanities/about-us/news/study-shows-the-lack-of-me-time-for-new-mothers/” target=”_blank” rel=”nofollow noopener noreferrer”>https://www.durham.ac.uk/research/institutes-and-centres/medical-humanities/about-us/news/study-shows-the-lack-of-me-time-for-new-mothers/

[2] MedicalXpress – Study shows lack of ‘me time’ for new mothers: https://medicalxpress.com/news/2025-09-lack-mothers.html [3] PubMed / British Journal of Psychology – Self-care in early motherhood: A qualitative exploration of sleep, exercise, and making time for oneself: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40614576/

[4] Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin – Definitions of Solitude in Everyday Life: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/01461672221115941 [5] Parents – Moms Are Experiencing a Big Mental Health Decline—Here’s What Needs To Change: www.parents.com/mothers-mental-health-declining-11746626″ target=”_blank” rel=”nofollow noopener noreferrer”>https://www.parents.com/mothers-mental-health-declining-11746626

Image generated by DALL-E 3

Leave a Reply